Some clarifications about the concept of objectivity used in autographic design.

A core tenet of critical data studies is that data are always subjective. The production of data involves countless arbitrary choices and assumptions that correspond to worldviews, problem framings, and ideologies. From the outset, data are always already interpreted. The field rightly critiques the notion of data as neutral references to a stable, universal reality. As Geoffrey’s Bowker’s famously notes, “Raw data is both an oxymoron and a bad idea; on the contrary, data should be cooked with care” (Bowker and Star 1999; Gitelman 2013).

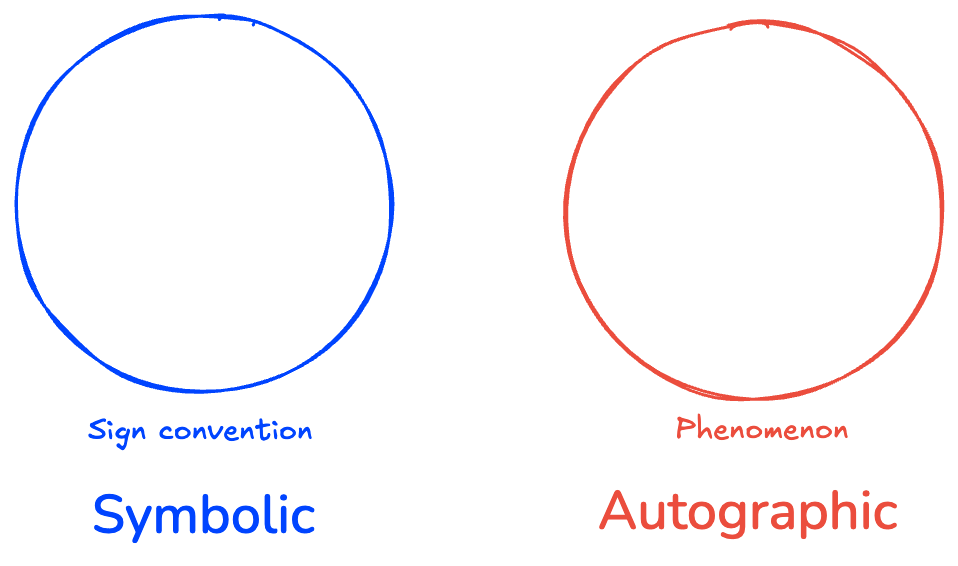

And yet, this is not the argument put forward in autographic design. On the contrary, from the perspective of autographic design, data are always objective. This is not a contradiction, since autographic design is less interested in the role of data as references to external truths than their own material reality. “Objective” in this case simply means that data are object-like (Offenhuber 2023, 12). They don’t represent things, but present themselves as things. One could call this objectivity in a weaker sense. Notably, the corresponding German word “sachlich” means both thing-like and pertaining to facts.

It is important because it acknowledges that data are more than references or signs – they are objects in their own right, bearing traces of data production that are often unrelated to what they are supposed to represent. The typos in a manually recorded data set may reveal the identity of the data entry operator regardless of the data content. Glitches and inaccuracies of geographical coordinates reveal whether the location was acquired by a cell phone, by a GPS receiver, derived from a street address by a geocoding algorithm, or has been manually measured from a map.

️️️️️️I could be accused of not paying enough attention to the epistemic charge associated with the notion of objectivity. I am not denying that data act as representations, signs, or references. I think, however, that we miss an important dimension by treating data solely as signs that represent truth claims. Autographic design invites us to stay with the phenomenon, linger a bit longer on its materiality, and consider structure, constellations, and configurations. The meaning of data, its semantic content, is not the only, and not always the best, way to investigate the worldviews, ideologies, and perspectives involved in data collection.

Neutrality: Since traces don’t refer to things but merely present themselves, they don’t make statements that could be judged as neutral or biased. However, if we take perception into account, traces present themselves differently; some are more expressive and evocative than others. In that sense, traces are not neutral. Furthermore, traces are usually produced and preserved by human-made devices. For example, to contemplate tree rings, one has to cut into a tree. The devices used to produce traces are designed with a particular problem definition in mind—they have a worldview. To get at the issues of bias, we can examine the modes of trace-making and are not limited to critiquing the resulting representations. Tree rings are a product of measurement, of a geometrical cut. The corresponding structures in the living tree could be better described as deformed nested tubes. The layers of earlywood (spring) and latewood (summer) do not have a sharp boundary; contrasts emerge on the cut surface after drying and sanding.

Truthfulness: Traces can only attest to the truth of their own presence. However, they are also the basis of interpretation, a semiotic process that establishes references and infers causalities. Initially, the smoke trails in the wind tunnel refer only to themselves, but they are nevertheless understood as clues of the movement of air more generally. Fidelity and resolution matter; a smoke wand that releases a fine-grained pattern of streams may be more useful than a single source of smoke. But they are never just references; their object-ness can never be ignored. The challenge is to resist the referentiality of traces, to examine them as a phenomenon before drawing conclusions.

Universality: Traces are never universal; they always result from a unique setting. They are complex assemblages involving various inscriptions, unlike signs, which involve more narrow claims of universality. However, a trace does not automatically become a sign, even if inferences are made based on its presence. As Umberto Eco notes, a semiotic convention is established once red spots on the forehead are more universally recognized as a symptom of measles and find their way into a medical treatise (Eco 1976, 17). At this point, we enter the space of signs and referentiality. However, it is not a one-way street: We can learn from textbooks how to interpret the appearance of plants, and based on our practice of probing and observing, we can move beyond symbolic conventions and appreciate the phenomenon as it presents itself (even if colored by our prior knowledge). Reductive simplifications can be a first step, as long as we don’t confuse them with the territory.

Bowker, Geoffrey C., and Susan Leigh Star. 1999. Sorting Things Out. MIT Press.

Eco, Umberto. 1976. A Theory of Semiotics. Indiana University Press.

Gitelman, Lisa. 2013. “Raw data” is an oxymoron. Cambridge Mass.: MIT Press.

Offenhuber, Dietmar. 2023. Autographic Design: The Matter of Data in a Self-Inscribing World. The MIT Press.